Gulf Chemical Warfare Depot, and Redstone Arsenal, 1941-1949

During the two decades between the end of World War I and the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, the United States withdrew into a strong protective shell consisting of isolationist, protectionist, and nativist sentiments. This urge to remain aloof from foreign entanglements had a decidedly adverse affect on the U.S. military, particularly the Army. The period between the world wars was a time of seemingly endless constraints on money, manpower, and materiel. By 1939, the U.S. Army was ranked nineteenth worldwide, behind Belgium and Greece.

Editors Note: This is a reproduction of a special study written by Helen Brents Joiner, a former Historian of the U.S. Army Missile Command’s Historical Division. We’ve attempted to reproduce this study for the web as it appeared in 1966, keeping all original language and punctuation. We’ve added photographs and links to other studies where we felt that the reader could benefit from these other studies.

Table of Contents

|

PART ONE CHEMICAL ACTIVITIES I. BEGINNINGS OF HUNTSVILLE ARSENAL Site Selection In early 1941 the Chemical Warfare Service had only one chemical manufacturing installation—Edgewood Arsenal, Maryland. As World War II drew closer to involving the United States, the Chief, Chemical Warfare Service requested the War Department to acquire additional facilities capable of furnishing an Army of 2,800,000 men with necessary offensive chemical munitions. Included in the supplemental appropriations that Congress passed to finance the Munitions Program of 30 June 1940 was over $57,000,000 for the Chemical Warfare Service, of which more than $53,000,000 was for procurement and supply. The selection of Huntsville as the site for a CWS arsenal stemmed from a visit by Maj. Gen. Walter C. Baker, a former Chief of the Chemical Warfare Service. On 8 June 1941, Lt. Col. Charles E. Loucks, soon to be Executive Officer of OC CWS, and a civilian engineer visited Huntsville Arsenal. Upon returning to Washington, they filed a 20-page report with Maj. Gen. William N. Porter, Chief, Chemical Warfare Service. The following week-end, General Porter and Col. Paul X. English reviewed the proposed location. From nine sites surveyed, ranging from West Virginia to Missouri (Huntsville, Florence, and Tuscaloosa, Alabama; Kansas City and St. Louis, Missouri; Memphis, Tennessee; Toledo, Ohio; El Dorado, Arkansas; and Charleston, West Virginia), the Chief, CWS recommended the one near Huntsville, Alabama, in an 18 June 1941 letter. Characterizing the Huntsville site as "more desirable, considering the matter as a whole, than any other location considered," he cited the availability of 33,000 acres of land "reasonably priced", the excellence of transportation facilities, labor conditions, construction materials, power supply from the Tennessee Valley Authority, operating personnel and raw materials, fuel, water supply, climate, health, living conditions, and sewage disposal. He conceded, however, that "as at all the sites seriously considered, it will be necessary to have a housing project." Activation |

|

Land Acquisition The Chemical Warfare Service immediately took steps to acquire the land by condemnation proceedings. When the Office of the Quartermaster General filed a petition on 23 July 1941 to this effect, the United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama, Northeastern Division, entered an order granting possession to the U.S. Government as of noon, 24 July 1941. The general procedure involved in securing the land was for an impartial expert—in this case, the Federal Land Bank of New Orleans— acting as a consultant to the Government, to appraise each tract. Negotiations between an OQMG representative and the landowner then began. Generally the owners accepted the evaluation and only a small percentage of the cases had to be taken into individual condemnation suits. In general, it may be said that the acquisition of land was conducted in a very orderly and expeditious manner, and not one case is on record where operations or construction had to be delayed because land was not acquired in time. The Government saved considerable money by allowing owners to remain on their land until crops were harvested if this did not interfere with construction. The removal process was spread out, therefore, over a period of time. No specific relocation program was needed, as the community absorbed the major portion of those displaced. Many of the people who formerly lived on the land obtained work with the construction contractors at a considerable increase in their annual income. First Contracts On 16 July 1941 the War Department signed a cost-plus-fixed-fee contract with Whitman, Requardt, and Smith of Baltimore, Maryland, for architectural and engineering services. A second contract of the same type followed on 21 July 1941—this one being with C. G. Kershaw Contracting Co., Birmingham, Alabama; Walter Butler Co., St. Paul, Minnesota; and Engineers Limited, San Francisco, California, for the construction of Huntsville Arsenal. |

|

During July contractors arrived and set to work assembling machines and materials. Col. Rollo C. Ditto, the first Commanding Officer of Huntsville Arsenal, arrived on 4 August 1941, and the next day, ground was broken for initial construction. According to one chronicler, "Huntsville became a bee hive of activity but lacked the corresponding orderliness." Thousands of workers streamed into the city, which did not have the facilities to accommodate them. For the duration, the Arsenal drew about 15,000 to 20,000 additional inhabitants to the town. |

|

|

By 14 September 1941, temporary buildings on the Arsenal were complete, and the new occupants moved in. Previously, the Commanding Officer and his staff had operated from the Huntsville National Guard Armory and the Huntsville High School. Personnel matters were handled initially in the Chamber of Commerce office in Huntsville for about two weeks, 10-21 July 1941, and then in the Armory from 22 July-13 September 1941. The initial plans for Huntsville Arsenal stipulated 11 manufacturing plants, four chemical-loading plants, plant storage, laboratories, shops, offices, a hospital, fire and police protection, a communications system, and utilities, including roads and railroads, necessary for the production, storage, and shipping of chemical munitions. Successive authorizations expanded the original plans considerably. The end result was tantamount to a complete city, which was for all practical purposes self-sufficient. Construction Funds The first funds arrived on 24 July, amounting to about $31.2 million, $1.65 million of which was earmarked for the purchase of land. As it turned out, the construction called for under the original directive actually cost $27 million, constituting a $4 million saving. Subsequent construction directives nearly doubled the original allotment during the next 12 months. By 1942 all construction had been placed under the Corps of Engineers. A 2 January 1942 directive from them authorized the building of a CWS storage depot having facilities for the storage of 20 million units, mainly in 200 concrete igloos. A 4 March 1942 dispatch added 150 igloos, six storage warehouses, and a toxic gas storage yard. Later in the same month, on 18 March, over $14.6 million was allotted for additional manufacturing and chemical-loading facilities. April instructions covered staff quarters, alcohol storage facilities, and troop housing. The directive received on 4 June 1942 was the last major authorization for manufacturing buildings and facilities. It amounted to almost $7 million. This project, together with previous ones, completed Plants Areas Nos. 1 and 2. Plants Area No. 3, costing over $4.1 million, contained 78 buildings comprising the facilities for filling HC (Hexachlorethane, white smoke) smoke pots, hand grenades, and base ejection shells. By September 1942, construction authorizations approached $71.5 million, counting those for the Gulf Chemical Warfare Depot. Many and varied construction projects were in progress throughout 1942 and most of 1943. No unusual conditions arose during the construction period to hamper the work to any great extent. When the Corps of Engineers moved off the Arsenal, in mid-1943, it turned over to the Chemical Warfare Service the largest chemical warfare arsenal in the world. By the end of World War II, the cost of all construction, including land, totaled $63,431,925. The original contracts and change orders thereto were closed on 9 October 1943. After that, from time to time, various additions and alterations became necessary. One of these was a prisoner-of-war camp to accommodate 655 prisoners. The Corps of Engineers constructed the original camp for 250 prisoners, the remainder of the camp being completed by POW labor. Layout The facilities of the initial construction authorization, except the Incendiary Bomb Filling Plant, were laid out in an area approximately two miles southwest of Madkin Mountain in a systematic and orderly design, since the Arsenal area was considered to be outside the passive defense zone. All additional chemical and manufacturing facilities and required utilities were arranged in a new area approximately two miles south of Madkin Mountain, but were disposed in an irregular pattern since the Arsenal area was at that time included in the passive defense zone. The Incendiary Bomb Filling Plant was isolated in an area adjacent to the eastern slope of Madkin Mountain near the south end. When additional smoke munitions filling plants were authorized, they were located adjacent to the old Incendiary Bomb Filling Plant with the CN-DM Plant. (Note: Known also as Adamsite and locally as "dirty mixture," it acted so rapidly that the victims were unable to pick up the grenades and throw them back, as they did occasionally with ordinary tear gas grenades.) An area of about eight acres on the right bank of Huntsville Spring Creek was set aside as a decontamination area known as the "boneyard." Here metal articles contaminated with mustard gas could be thoroughly decontaminated by burning in a wood or oil fire, if sufficient air was provided in long pipes or partially closed containers. Destruction or decomposition of Lewisite was not so effective. Chain of Command Huntsville Arsenal was a Class IV installation. As such, it was responsible to two superiors. The Fourth Service Command exercised administrative control over certain functions. The technical service—in this case, the Chemical Warfare Service—controlled other functions. Until December 1944, the Industrial Division, Office of the Chief, Chemical Warfare Service, was Huntsville Arsenal’s immediate "higher authority." After that date, a paper reorganization of OC CWS required Huntsville Arsenal to report to the Deputy Chief, CWS. Actually, no change in administration took place, as Arsenal and Industrial Division personnel continued to maintain their contacts on the same basis. In November 1943, all service units supplied to the Chemical Warfare Service by the Fourth Service Command were united to form the 4468th Service Command Unit. The combining of the Medical Department, the Finance Department, and the Signal Corps into this unit was designed to facilitate administration of the Service Command personnel. |

|

II. ORGANIZATION OF HUNTSVILLE ARSENAL General Summary Construction was the first order of business at Huntsville Arsenal but, so fast on its heels did production follow, prodded by the pressure of war, that the two programs overlapped for almost a year. When the first Commanding Officer of Huntsville Arsenal arrived in August 1941, he immediately set up an organization to expedite construction. The initial organization was simple, consisting of an Engineering Division as its major element, and a number of specialized divisions such as Civilian Personnel, Adjutant, Procurement, and Signal. All reported directly to the Commanding Officer. By January 1942, the transition to the production phase began with the grouping of the major elements for operations, planning, and maintenance under the Chief of the Operations Division. The rest of the functions reported directly to the central coordinating agency, the Executive Office. The Executive Office controlled and coordinated the functions of the various divisions and staff offices in accordance with the directives of the War Department; the Chief, Chemical Warfare Service; the Fourth Service Command; and the Arsenal commander. During 1942 a number of organizational changes took place. A basic concept underlying them was the "task force" principle. Application of this concept made for the self-sufficiency of each operating element in that each would have an engineering, personnel, property, transportation and storage section to support it. While this arrangement decentralized responsibility to lower echelons, it also increased administrative costs by duplicating some functions that had been assigned on an Arsenal-wide basis to operating and staff divisions. Coordination between the Operations Division, Engineering Service Division, and the Procurement and Production Control Division became an exacting problem that was accentuated by the fact that production schedules, plant capacities, availability of personnel, and materiel were in a constant state of flux. In September 1944, in an attempt to strengthen the production planning function, which ultimately determined the success or failure of the production organization of the Arsenal, the Commanding Officer established separate divisions for procurement and for production planning. When this reorganization did not fully meet expectations of efficient operation, the Operations Division absorbed all production planning in an effort to promote liaison between the two functions. The Chief of the Operations Division was then responsible for at least two major phases of the production program—planning and execution. After this March 1945 consolidation, efficiency appeared to improve. Engineering Division The Engineering Division, one of the original Huntsville Arsenal elements, was organized on 16 August 1941 with Lt. Col. W. J. Ungetheum as Chief. It operated from the State National Guard Armory in Huntsville until mid-September, when all Arsenal offices moved to Building T-158 in the temporary administration area. The division was specifically charged with supervising and coordinating the work of the architect engineers, the prime contractor, and the Construction Quartermaster (later, Area Engineer); with supplying adequate designs for all production and utility facilities; with supervising the procurement of equipment; with inspecting all structures and process equipment; and with supervising all testing and test operations. Operations Division As of 16 January 1942, the Engineering Division was redesignated the Operations Division. The mission of the division included the completion of all authorized plants; the production of all munitions; advising the Procurement Division of the components required to meet production; and the maintenance of plants and utilities and operation of utilities plants. On 28 February 1942, the Arsenal’s first production emerged from a pilot line for M54 incendiary bombs set up in Warehouse 642. This production continued intermittently, as components were available, until 21 April 1942, when fire destroyed the entire plant and equipment. On the morning of 8 December 1941, General Ditto, now promoted, announced to his staff that the date of initial operation of the first H (crude mustard gas) plant was April 1942 instead of July. This goal was met when, on 7 April 1942, the first mustard gas was made at Plant No. 1, Building 311. When the first H plant went into operation, the Chemical Plants Department was set up under Operations to supervise the construction and operation of all chemical manufacturing plants. At about the same time, all munitions filling plants, with the exception of the Incendiary Bomb Filling Plant, came under the new Munition Filling Plants Department headed by Maj. R. L. Swindler. The Incendiary Bomb Filling Plant, later renamed Grenade Filling Plant, reported to the Chief of Operations until July 1942 when it too went under the Munition Filling Plants Department. In August 1942, with the authorization of smoke munitions filling plants and a tear gas (CN-DM) plant, it joined those plants to form the Smoke and Incendiary Loading Department. Col. L. W. Greene was appointed Chief of Operations on 15 June 1942 when Colonel Ungetheum transferred to Rocky Mountain Arsenal. Engineering Service Early in March 1942, the Operations Division organized an Engineering Service Department to operate utilities and maintain equipment in buildings on the Arsenal. On 15 June 1942, this function became a separate and parallel division under Lt. Col. R. A. Phelps. The division thus performed many of the duties ordinarily performed by the Post Engineer or the Quartermaster Officer, such as the operation of the Tennessee River Docks, a sawmill, a limestone quarry, and a rock crusher. A special function was the handling of contaminated wastes and rejected toxic-filled munitions. The first Engineering Service Department office was set up in Building 427, a maintenance shop, on 26 March 1942. (Division headquarters was later in Building 432, Plants Area No. 1.) Among its first tasks was to provide water and electric power and steam supplies for new plants. The first central steam station was not yet complete when the first manufacturing plant began operation. Therefore, three 125-horsepower Scotch marine boilers, installed on temporary settings at strategic locations, supplied steam during the summer of 1942. As the Allied forces increased their use of screening and signaling smoke, Huntsville Arsenal expanded its facilities for making these munitions. Adequate supplies of steam and compressed air were essential to these plants, but manufacturers of compressors, boilers, and stokers were swamped with orders of equal or greater importance. Nevertheless, relying on the resourcefulness of its employees, the Arsenal set out to equip a central station air compressor plant and a steam plant. Some ingenious scavenging brought boilers to Huntsville from Birmingham, where they had been built in 1903. Stokers to fit these boilers were found in a plant in Yonkers, New York, where they had been installed in 1905. "Nitrate Plant No. 1," standing idle at Sheffield, Alabama, since World War I, contained seven 4-stage Nordberg compressors designed to compress hydrogen or ammonia to a pressure of 1,400 p.s.i. After being brought to Huntsville and re-worked into 2-stage machines, these compressors furnished 235 pounds of central air for the plants manufacturing smoke munitions. Property The Property Division was activated in July 1941, when Lt. L. A. Parks was appointed Property Officer. After August 1941, the Property Officer also had the additional duty of being Acting Quartermaster. The initial assets consisted of a small amount of storage space in a barn on Jordan Lane and one truck. By October 1941, a receiving and checking department began to emerge as a separate function, as did a stock record section. In February 1942, the Delivery Department began operating in the Wynn Jones barn near the old Motor Pool on Rideout Road, and in March 1942, regular warehousing of materials began in Plants Area No. 1. A Salvage Yard was organized in April 1942. Beginning as a pile of lumber not far north of the junction of Martin and Mills Roads, the yard covered eight acres by the end of the war. Huntsville Arsenal was selected as the first CWS arsenal to use War Department Shipping Documents, a new method for the transfer of property accountability. The Smoke and Incendiary Loading Department Branch Property Office, activated on 9 November 1942, pioneered this effort. Transportation The Commanding Officer, Colonel Ditto, started the transportation workload at Huntsville Arsenal by bringing with him Chevrolet passenger car #12103, the first vehicle at the Arsenal. The transportation function was originally included in the Property and Acting Quartermaster Division, in September 1941. In April 1942, the Transportation Division was activated as a separate organization, with Maj. Roy A. Burt as its first Chief. By the end of 1943, the division had 436 vehicles, 7 diesel locomotives, and about 225 cars of rolling stock. The Huntsville Arsenal Railroad was among the first construction work begun on the arsenal so that it could deliver heavy equipment and supplies to other construction areas. The first track was laid in September 1941. Two classification yards, one for the Southern Railroad on the west side and one for the Nashville, Chattanooga, and St. Louis Railroad on the east side, were completed in November 1941. Tracks connected the two yards, about seven miles apart, through the proposed plants area in December 1941. The lines to the Gulf Chemical Warfare Depot and to Redstone Arsenal were also completed in December 1941. The distance to the Depot was about six miles, and to Redstone Arsenal, about 10 miles. The complete system consisted of about 75 miles of track. The west classification yard was closed down in August 1943. Finance All funds allotted for the operation of the Arsenal were spent by the Procurement and Production Control Division. Activated in July 1941 as the Procurement, Cost, and Fiscal Division, production control was combined with it in April 1942. The fiscal and cost function was separated from the Procurement Division in October 1942 and set up as a Fiscal Division with Capt. I. M. Breller as Chief. Payroll functions were the responsibility of the division until March 1943 when they were transferred to the Civilian Personnel Division. Prior to activation of a Finance Office at Huntsville Arsenal, also in March 1943, the Fiscal Division processed all commercial accounts for payment to the Atlanta Finance Officer. The Arsenal’s financial growth was rapid. The original operating allotment of 12 July 1941 was $17,000, and the original allocation for the first manufacturing order was $1 million on 5 October 1941. By FY 1944, there was an allotment of $30 million to cover manufacturing orders from the CWS, exclusive of allotments from other services or special overhead funds. Payrolls ran approximately $1 million a month. With the growth of activities, the Arsenal sold certain manufactured items and by-products which entailed some adjustments in the usual "one way" accounting system. Receipts for such sales totaled about $1 million in 1943. The Finance Office paid the accounts for services and commodities of Huntsville Arsenal, the Gulf Chemical Warfare Depot, Redstone Arsenal, and the Area Engineer. This included all military personnel, civilian personnel, and commercial accounts. The office issued all war bonds bought by personnel of the two 4rsenals and the Depot. It also collected all funds from and had charge of the post laundry and all salvage sales. Military Police On 28 August 1941, the 222nd Military Police Company arrived from Edgewood Arsenal, with a strength of 4 officers and 80 enlisted men. On 11 April 1942, the Military Police Detachment was activated at Huntsville Arsenal with a strength of 1 officer and 93 enlisted men. These outfits operated under a battalion setup until 1 July 1942, when the Corps of Military Police Detachment was activated, consolidating the organizations. Medical Detachment Also on 28 August 1941, a Medical Detachment of six men arrived and was assigned to the 222nd Military Police Company for administration. The first sick call on post was held in a tent on 6 September 1941. On 8 November 1941, the first sick call was held in Building T-144, which had been designated the Post Hospital. The hospital moved to Building 117 on 1 May 1942, and the first nurse reported for duty on 16 May. The Industrial Medical Service was established on 25 May, and the Dental Clinic opened on 10 June in Building 117. The first baby was born in the Station Hospital on 16 August 1942. Huntsville Arsenal provided hospital facilities for Redstone Arsenal, which maintained only an industrial dispensary that did not provide bed care. The Medical Department was under the supervision of Headquarters, Fourth Service Command, Atlanta, Georgia. As Huntsville Arsenal was located in one of the most malarious areas in Alabama, a malaria control program was started on 1 October 1941. The TVA system had created large areas of water surface that extended into the arsenal area, providing an excellent breeding ground for anopheles mosquitoes. Mosquito control thus required varied measures, some of which were carried out by POWs. The control of industrial wastes also presented several problems. Many of the chemical processes used on the arsenal produced waste products of an unusual nature that required special treatment in order to hold stream pollution to a minimum. Intelligence As the Construction Quartermaster (later, the Area Engineer) was responsible for the security of Huntsville Arsenal until its completion, the former activated a guard force and a fire department and performed the duties normally expected of a post intelligence office. In January 1942, Lt. Col. A.T. Brice was assigned to the newly activated Safety and Military Intelligence Division. The peak of construction was reached in February when 15,000 construction workers were employed by Kershaw Butler Engineers, Ltd. Since this type of work, especially in wartime, attracted a large number of "floaters," many of whom had criminal records, the Area Engineer had plenty to do. As the CWS took over plant jurisdiction, it activated a Civilian Auxiliary Military Police in April 1942, and assumed control of the Fire Department in June and July. The Post Intelligence Officer was responsible for all investigations in any case where enemy activity was suspected. He also handled cases normally thought of as police work. Reported incidents varied from minor theft of personal property to acts of sabotage. Safety The Industrial Safety Division was activated on 31 October 1942, with 1st Lt. Walter T. Harper, Jr. assigned as Chief. The division supervised accident prevention throughout the Arsenal. Although most personnel at the Arsenal were inexperienced in plant work, and, moreover, many could not read or write, they nevertheless became instilled with safety consciousness. Special safety equipment included such protective items as gas masks, rubber aprons, flame-resistant clothing, impregnated clothing for protection against mustard, special goggles, gloves, and toe guards. Special impervious clothing was designed that permitted no ventilation, but this could be worn only for short periods. Frequent fire drills were held, and all personnel were required to demonstrate proficiency with the gas mask and to go through the gas chamber periodically. All personnel had to carry masks in designated zones. The fire hazard at Huntsville Arsenal was quite different from that in most industrial plants. Plants Areas 1 and 2 each contained a building that presented a considerable fire hazard, as did the whole Smoke Incendiary Loading Department. Another hazard not generally associated with an industrial plant arose from the large amount of grassy area on the arsenal. During the dry season, grass fires constituted a serious problem. Many fires were started from locomotives passing on the tracks near the arsenal. There were eight fatalities in the Operations Division—seven civilians and one officer—from the start of operations through July 1945. In colored smoke operations, out of a total of 177 recorded fires, 149 of them occurred with yellow mix. Sixteen explosions occurred in pressing violet mix, as compared to one or two explosions in each of the other colors. During 1942-43, until filling equipment and the ventilation system were improved, the mustard filling plant was the source of most of the lost-time accidents. The immediate application of M-4 and M-5 ointments for mustard burns and BAL (British Anti-Lewisite) ointment for Lewisite proved very effective as decontaminating measures, however. Inspection The Inspection Office at Huntsville Arsenal was established on 1 February 1942. It was this office’s responsibility to inspect incoming materials to be used in the manufacturing processes at the Arsenal and to inspect all chemical agents and munitions manufactured at the Arsenal to insure that they met specifications. It proof-fired incendiary bombs manufactured by Huntsville Arsenal and by five outside manufacturers and proof-tested all chemical mortars issued for field use. Among the main accomplishments of the office was the development of an arsenic waste disposal system, a field disposition method for 4.2-inch chemical mortar live duds, a static bomb proof-testing method, and an accelerated aging test method. The first 4.2-inch chemical mortar shells were proof-fired at the Arsenal in January 1943. In May 1943, an Air Corps Detachment, consisting of three officers, three enlisted men, and two planes—a B-26 and an L-20—was stationed at Huntsville Arsenal. Its mission was incendiary proofing. M47 100-pound IM-filled bombs (Isobutyl methacrylate, polymer AE, a substance used to thicken gasoline for incendiary purposes) were the first dropped. Static firing also began with this type of bomb. An additional proofing range, known as the South Bombing Range, was completed about this time. By July 1943 a 500-foot concrete bombing mat was finished, and the first skate tests and 4,000-foot drop tests on M50 incendiary bombs were conducted. A simulated village, consisting of some 50 wooden shacks with three streets—one of large stone, one of gravel, and one of dirt—had been constructed. Known as "Little Tokyo," this village was used in testing the M47’s. In addition, two 4.2-inch chemical mortar ranges with prepared positions, observation dugouts, and range communications were completed, and proofing of the mortars began in August 1943. During the first two months of 1944, with most of the shacks in Little Tokyo obliterated, a 200-foot wooden structural target was erected for the proofing of 500-pound M76 incendiary bombs. It was during this period that the bomb was first static-fired and a method of dud disposal developed for it. Judge Advocate Lt. Col. Heber H. Rice was appointed Staff Judge Advocate on 3 October 1942. One of his first acts was to try to obtain jurisdiction over Huntsville Arsenal for the U. S. Government from the State of Alabama. In response, the Governor of Alabama issued a patent, dated 9 November 1942, ceding exclusive jurisdiction of Huntsville Arsenal and the contiguous Redstone Ordnance Plant to the Federal Government, except for 63 of the approximately 300 tracts contained within the reservation. After further negotiation, a final patent, dated 9 April 1943, ceded exclusive jurisdiction to the whole reservation. This prevented conflicting jurisdictional claims from arising, such as would have been the case if the city and the state had continued to exercise rights on the reservation concerning such things as building permits, hunting license fees, and similar matters. When the Legal Division was established on 8 February 1943, Colonel Rice became Chief of it, in addition to being Staff Judge Advocate. Signal The telephone equipment and plant for the Arsenal and Depot were valued at $190,500 at the end of the war. Of this amount, switchboards accounted for $24,275; power plants $6,000; and outside plant, $131,000. The cost of labor for outside plant construction was $173,719.73, of which the Southern Bell Telephone and Telegraph Co. was paid $68,129.20 and the Area Engineer was reimbursed $104,590.53 for labor used in buried cable installation. Installation, moves, and temporary service furnished by Southern Bell amounted to $77,904.02. Thus, the cost of the Huntsville Arsenal and Gulf Depot telephone system amounted to $251,623.75, exclusive of material used, labor, and civilian personnel on Signal Corps payrolls. Of the 170,000 feet of telephone cable installed by the end of the war, 35,000 feet was aerial and 135,000 was buried. In one instance, a cable buried in low swampy land was discovered to be going slowly out of service. Telephone, telegraph, and TWX service to Redstone Ordnance Plant was imperiled, as was all service to the Gulf Depot. The impaired cable was found to be under several feet of water near a creek that was aerially spanned. Since the cable could not be repaired while under water, a valve was inserted in the aerial cable above the creek, and nitrogen was forced into the cable at a sufficient pressure to counteract the pressure of the water seeping into the cable from a hole caused by electrolytic action on a factory defect in the cable. The cable remained in service in this state for 11 weeks, until it could be replaced by an aerial cable. Public Relations From the construction days of August 1941 until April 1943, Huntsville Arsenal was practically without a public relations program. Relations with "outside citizens" and news services were at a very low ebb. The editor of a local newspaper reportedly instructed his staff to quit calling the Arsenal for items of potential interest because a telephone request drew only a mild kind of insult. As the Chemical Warfare Service operated on a rather secret basis, Arsenal officials were necessarily reluctant to give out information of any kind. Since practices and procedures were not clearly defined as to what to say and what not to say, a "say nothing" policy prevailed. After a Public Relations Officer was appointed in April 1943, relations steadily improved. Supply In October 1944, the Ordnance Department designated Huntsville Arsenal as a key supply point for requisitioning, storing, and issuing automotive spare parts and supplies. Redstone Arsenal, the Resident Engineer at Redstone Arsenal, Gulf Chemical Warfare Depot, Courtland (Ala.) Air Base, and Gulf Ordnance Works at Aberdeen, Mississippi, drew on Huntsville Arsenal for their supplies. Post Exchange An innovation in the Post Exchange operation was the cultivation of a truck garden, products from which were used in the cafeteria and sold in the PX. Another venture was a pig-raising project. The PX owned 90 hogs, fed mostly by swill from kitchens. The pigs were to provide pork for the cafeterias. A farmer was employed to care for the hogs and tend the "Victory Garden." Operative during 1943 and the spring of 1944, the farm was discontinued in May 1944 as being too costly, the loss on it amounting to $576.13. Personnel |

|

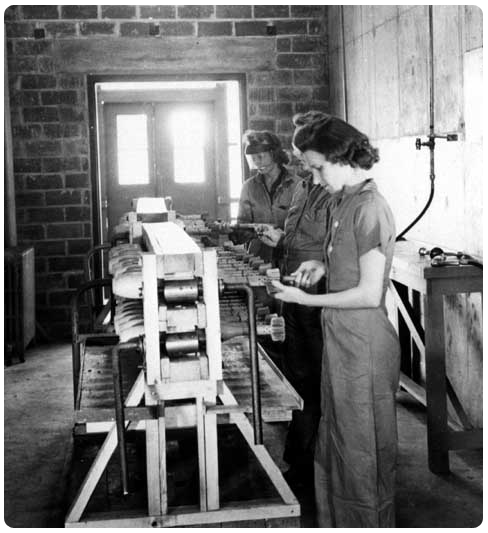

The earliest records of Arsenal personnel, dating back to March 1942, showed a strength of 699 civilian and 185 military personnel. Early in 1942, the Civil Service Commission notified the Arsenal that it could no longer furnish applicants for existing vacancies, so the Arsenal proceeded to locate its own employees. Selected applicants were sent to Edgewood Arsenal for training in the methods of munition and gas manufacture. This group became the cadre for training other personnel, mostly on the job. When the Arsenal opened, all ungraded employees were hired at temporary rates of pay based on grades at Edgewood Arsenal, pending the results of a local wage survey. It was not until August 1943 that the Army Service Forces accepted the Arsenal’s proposal for its wage structure. The initial need for civilian personnel was limited to engineers and officer workers, but, as production units were activated, the need for production, maintenance, and more administrative types accelerated rapidly until Huntsville Arsenal reached its peak of 6,707 employees in May 1944. Over 90 per cent of the work force was civilian. There were some 15,000 employees on the Arsenal in January 1943, counting contractor personnel and the Area Engineer people engaged in construction. Also, the Arsenal was operating on a 24-hour basis at that time. The distribution of the types of workers was fairly constant in that approximately 9 per cent of the personnel were unskilled; 48 per cent semiskilled; 18 per cent skilled; and 25 per cent administrative or graded employees. A representative sample recorded in September 1944 showed 26 per cent white female, 11 per cent colored female, 52 per cent white male, and 11 per cent colored male. For a long time, the Arsenal maintained a working ratio of white and colored employees almost equal to the population ratios. Military strength reached its zenith (580) in October 1942. In December 1943, a number of WAC’s arrived for administrative duty. Enlisted men were used primarily as security forces. None worked on production or maintenance projects. As of 1 May 1945, approximately 700 employees were on military furlough or had resigned to enter the armed forces. This amounted to about 12 per cent of the work force. Commanders Commanders of Huntsville Arsenal and their dates of service: Col. Rollo C. Ditto - 4 August 1941 to 24 May 1943 (Brig. Gen. as of October 1941) Col. Geoffrey Marshall - 24 May 1943 to 3 August 1945 Col. E. C. Wallington - 3 August 1945 to 20 July 1946 Col. Sterling E. Whitesides, Jr. - 20 July 1946 to 22 December 1947 Col. James M. McMillin - 22 December 1947 to 22 February 1949 Lt. Col. Allen H. Williams - 22 February 1949 to 30 June 1949

|

|

III. WARTIME WORKLOAD Huntsville, like the other CWS arsenals, manufactured toxic agents, smoke, and incendiary materiel, and with these filled shells, grenades, pots, and bombs supplied, usually, by the Ordnance Department. Representative munitions are discussed below.

Mustard Gas Chlorine Plants Two chlorine plants generated chlorine for the manufacture of mustard gas (usually referred to as "H"). Each plant could produce 50 tons of gaseous chlorine or 45 tons of liquid chlorine and 56 tons of 50 per cent caustic soda per 24 hours. The fusion plant, which cooked 50 per cent caustic into solid caustic, could produce 75 tons a day, although rated at only 65. Preliminary operations began in May 1942, with production continuing until July 1945. Manufacturing |

|

Six mustard-manufacturing plants were constructed at Huntsville Arsenal. The first four plants were in Plants Area No. 1, and the others in Plants Area No. 2. Each plant consisted of a sulfur monochloride building, an ethylene generator building, and a mustard reactor building (note: soon after the mustard gas manufacturing plants began operation, it became evident that the renewal of reactor coils was proving costly and time-consuming). |

|

|

The Engineering Service Division was able to develop a new coil, at little additional cost, with triple the life of the old coil. The original design of each plant was for the manufacture of 24 tons of Levinstein H but it was soon found that 40 tons a day could be achieved. The mustard manufacturing plants were shut down between 23 and 28 May 1943, and production officially ceased on 28 May 1943. But, in June 1945, the Arsenal was alerted for possible resumption of mustard manufacturing and in July, Plants 2, 3, and 4 were readied for this eventuality. In fact, five batches of sulfur monochloride had already been prepared, and further work was awaiting the arrival of alcohol when all preparations were halted, then canceled, by the imminence of the Japanese surrender. Filling Construction of two mustard gas filling plants was authorized on 24 July 1941, and after Pearl Harbor a third was authorized but was never completed, being ultimately adapted for incendiary oil munitions filling. The first H filling plant, Building 471, was ready in March 1942. The first item scheduled for production was 105-mm M60 shells. These were first produced in April 1942 and were filled with mustard gas manufactured at Huntsville Arsenal. Both the H filling plants operated until March 1944, at which time they were placed in standby. The No. 2 Plant, Building 481, was reactivated in October 1944 to fill an M70 bomb schedule. Deactivated in January 1945, it reopened in August to fill 5,556 more M70 bombs. The fact that mustard gas was never used in the war made for much variance in the program and schedules. Employees working with mustard gas had to wear special clothing and take extra precautions to avoid burns. Prompt action was mandatory because no preventive measures were known to be effective between the 10-15 minutes after exposure and some 24 hours later when blisters developed and were treated as any second-degree burn. Nor was any preventive treatment known for irritations of the eyes and respiratory passages following exposure to low vapor concentrations of mustard. Workers had to bathe and change clothing before being allowed to leave the plants. The filling of M47A2 bombs began in October 1942, but as the assembly lines for filling shells were not adequate for filling bombs, the setup soon proved unsatisfactory. With fatigue and forgetfulness often present, it was not long until some operator tried to drop two charges into one bomb. This dumped several gallons of mustard on the floor and thoroughly contaminated the conveyor rolls and adjacent equipment. Since the equipment and concrete floors were very difficult to decontaminate, the situation went from bad to worse despite safety devices installed on the filling machines. Consequently, the filling equipment became contaminated to the point that it was always "hot." Many employees suffered from severe cases of eye and throat irritations. Eye irritations reduced vision to a fraction of normal, and there was no cure except rest. Throat irritations produced a dry cough that kept many an employee awake at night. In December 1942 and January 1943, some 30 new officers from Officer Candidate School were assigned to the plant to bolster the supervisors, who had been pretty well exhausted. These officers then worked themselves so strenuously that a number had to be hospitalized for general debility and eye and respiratory irritations. The filling of the Navy bomb MK42, begun in January 1943, was the most hazardous operation undertaken in mustard filling. The bombs tilted easily on their assembly line pallets, and also their screw closures tended to leak. The net result was a large number of "hot" bombs. By the time 11,856 bombs were filled, the incidence of incapacitated employees had risen so high that the plant was closed for cleanup. The filling equipment, conveyors, piping, and air ductwork were all scrapped to permit a complete rehabilitation of the space.

Lewisite Thionyl Chloride Only one Thionyl Chloride Plant was constructed at Huntsville Arsenal. Its purpose was to supply a drying and chlorinating agent to be used in the treatment of crude Lewisite, to decrease sludge formation. Completed in April 1943, it was erected in Plants Area No. 2 adjacent to Chlorine Plant No. 2. Designed to produce three and one third tons of thionyl chloride a day, it could produce as much as five tons a day. Production began on 15 March 1943, was discontinued on 4 October 1943, and was never resumed. Arsenic Trichloride Another plant contributing to the manufacture of Lewisite was the Arsenic Trichloride Plant. Consisting of an arsenic trichloride reactor building, a sulfur monochloride manufacturing plant, and a sulfur dioxide disposal system, the plant had a capacity of about 30 tons a day. It began operating on 20 March 1943 and continued until 11 November, when it was placed in standby. Subsequently its equipment was removed to make way for a plasticized white phosphorus plant. The Arsenal originally intended to have six Lewisite plants but actually operated only four. Plants No. 5 and No. 6 were completed except for minor items of equipment but were never activated, so the equipment was removed for other use. Plant No. 1 began operating in November 1942, followed by Plant No. 2 in December, and Plants No. 3 and No. 4 about May 1943. Plant No. 4 was not operated continuously because of a shortage of arsenic trichloride. All manufacturing operations were permanently halted on 30 October 1943, and the plants were declared surplus in 1944.

Phosgene One plant was involved in manufacturing phosgene. Its facilities included a carbon monoxide-generating plant, a catalyser building, a ton-container filling shed, various storage tanks, and an office and locker room building. The expected output was 30 tons a day, but production attained during one month averaged better than 40 tons a day. Production lasted about a year, from 11 February 1944 to 17 January 1945. The phosgene filling plant was located some 50 yards from the manufacturing plant. It had storage space for about 800 empty bombs. It had six filling stations, each capable of filling 40 bombs each 8-hour shift. Filling of 500-pound M78 bombs lasted from 15-27 April 1944. Filling of 1,000-pound M79 bombs started on 28 April, continuing until 17 January 1945, when all the phosgene was used up.

White Phosphorus Huntsville Arsenal had one White Phosphorus Filling Plant, occupying an area approximately 1,000 feet wide and 2,000 feet long on the west side of Plants Area No. 1. Construction began in November 1941, and operation started on 15 May 1942, ceasing on 14 August 1945. Ten different munitions were filled during that time, including artillery and mortar shells, grenades, and igniter tubes. The work in the filling department could be quite hazardous, requiring protective clothing. For example, in filling MI5 hand grenades, the white phosphorus was apt to flare out on the operators. Practically every operation was a hand operation in this program, which caused the White Phosphorus Filling Plant to have many difficulties. |

|

A number of accidents also occurred during the filling of the M46, M47A1, and M47A2 100-pound bomb. The oil used in leakage testing of the bomb left vapor in it, and when the "phossy" water was putinto the bomb before filling, the vapor often ignited with a loud report. |

|

|

The white phosphorus plant trained its personnel to do several different jobs, however, so this rotation formed a relief system for the more hazardous and difficult operations. Until September 1943, all phosphorus-filled components were salvaged to reclaim the phosphorus. The empty containers were then sent to the disposal pit for decontamination by burning. However, the labor cost made this practice prohibitive; and after accidents occurred, all phosphorus-filled rejects were sent to the "boneyard," where the phosphorus was burned.

Carbonyl Iron The Carbonyl Iron Plant at Huntsville Arsenal was established solely to serve as a standby plant in the event that the only successful plant then in operation, that of the General Aniline Works at Grasselli, New Jersey, should be put out of action. The H. K. Ferguson Co., awarded a contract on 22 October 1942, erected 17 buildings to house the plant. Then a plant at Shreveport, Louisiana, was dismantled, and the equipment, plus some additional, was moved to Huntsville Arsenal and installed. This happened because the low-pressure plant that the Ferroline Corporation had constructed at Shreveport failed to produce. The Defense Plant Corporation then took it over; transferred it to the Chemical Warfare Service, and moved it to Huntsville Arsenal. General Aniline was retained to redesign the plant for pressure operation and to render technical assistance until it was in successful production. Located in Plants Area No. 2 near Chlorine Plant No. 2, from which it obtained the hydrogen necessary for its processes, the plant had a daily capacity of 1,500 pounds of carbonyl iron. Instructions were to produce 125,000 pounds of carbonyl iron and then put the plant into standby. Production began on 9 July 1943. When the quota was reached on 26 October 1943, the plant was shut down.

White Smoke Munitions Pots Production of the M4 white smoke pot began in Building 638 in November 1942 and ended in August 1943. The designed daily capacity of this plant was 7,500, but construction of a larger line, Building 1050, which began operation in May 1943, almost doubled this to 13,500. Production stopped abruptly on 17 August 1943 when fire destroyed Building 648. Two thousand rejected pots stored in Warehouse 648 were ignited when a girl employee, dismantling pots, threw an ignited fuze lighter into a pile of starter cups, resulting in the death of the girl and the loss of the building and its contents. In January 1944, production was resumed, to run until April 1944, when an improved pot, the M4A2, replaced the M4. Production of M4A2 pots halted in November 1944, to be resumed in May 1945. The rate was 90,000 pots per month until V-J Day. First-run production of the M1 smoke pot lasted from 22 March 1943 to 30 April 1943. The second run extended from 10 August 1943 to 15 January 1944. The designed capacity at Building 668-2 was 9,000 pots a day and 18,000 pots at Building 1050. Output reached 21,000 per day at the latter after remodeling.

Shells The M89 smoke shell was a 75-mm artillery munition initially developed at the request of the British. Production of these shells was very erratic and troublesome throughout 1943. As there was no gun available at Redstone Arsenal to test the munition, there was a delay of several weeks between manufacture and proof-testing, which left the production people "in the dark" as to what their problems were. Early in 1944, a group of officers made a trip to a Canadian plant that was successfully producing the shell. The know-how gained there and the acquisition of local proofing facilities generally simplified matters. When production, having ceased in the spring of 1944, was resumed in June, a successful shell was attained and a considerable number of units produced throughout the rest of the year. The M88 shell was also an HC smoke shell, of 76-mm diameter, designed to be fired from an artillery weapon. Preparations began for the production of the shell in June 1944. As the work was largely a repetition of that done in the previous year for production of the M89, production techniques were well developed. Production ended in November 1944, the largest number of shells—98,032—having been produced in August. Grenades Another white smoke munition was the M20 rifle grenade. Initial production averaged 6,000 grenades per shift. Improved methods and equipment upped this figure to 15,000. Production started in December 1943 and continued intermittently until February 1945. Canisters Late in 1942, Huntsville Arsenal received a rush order to prepare thousands of smoke canisters for immediate use by troops in the field. First tests of the canister revealed that the metal case did not admit sufficient air for efficient combustion, but it was found that three series of holes in each can would permit satisfactory burning. To the Engineering Service Division fell the task of punching holes in the many thousands of cans already shipped in. Laborers, carpenters, painters, and anyone else who could swing a hammer and handle a punch were put to work on a 3-shift, 7-day basis. Result: the canisters were shipped to the field ahead of the production schedule.

Tear Gas There were 243,020 M7 CN (tear gas) grenades produced at Huntsville Arsenal during the December 1943 - April 1944 period when these were manufactured. M6 CN-DM grenades totaled 252,348 during the two months (April-May 1944) that they were manufactured.

Incendiaries By 30 June 1945, four different types of incendiary oil munitions had been produced at the Incendiary Oil Plant—M47A2, M4 cluster (M69), M76, and the M19 cluster (M69). M76 bombs were filled with PTI gel, an incendiary fuel based mainly on "goop" and IM gasoline. "Goop" was a mixture of magnesium particles and asphalt used in incendiary bombs. The bombs were placed in open storage and, during the warmer months, the gel within the bombs warmed up and expanded to such a degree that the burster well collapsed. Subsequent experimentation revealed that, if a bomb was subjected to a temperature of 150 0F. for three hours, collapsing of the burster would very often take place. Fires originating in PTI gel, often spontaneously, were exceedingly difficult to extinguish. Experiments with various materials showed that a 50-weight oil was most effective. The oil had to be applied immediately, however, for if the fire got too hot, the oil also would ignite. The M54 thermate incendiary was a 4-pound bomb manufactured at Huntsville Arsenal for less than two months. The main processing building, activated for production on 12 March 1942, burned down on 21 April 1942 and was not rebuilt. Pine Bluff Arsenal and National Fireworks manufactured the munition after that. The AN-M14 grenade was a modified thermate incendiary that could generate enough heat to melt through a sheet of 3/8-inch steel. Huntsville Arsenal had facilities for producing 12,000 of these per 8-hour shift. Production ran from August through December 1943.

Colored Smoke Grenades The daily capacity of the M16 colored smoke grenade plant was about 15,000 grenades per 24-hour work period. The program, begun in October 1942, continued until 16 November 1943 when the M18 grenade replaced it. The same production facilities and equipment were used. As the shift officer’s log book laconically stated, "Personnel were instructed to clean the area from noon until 2:15 p.m. when the order was received to begin production of M18’s." The first M18 colored smoke grenade (violet) was produced that same day; the last, on 8 May l945. The fill and press building could produce 6,000 grenades per 8-hour shift and 10,000 could be assembled during the same time. The dye used in the grenades colored the workers’ clothing and stained the skin. Reportedly, it was not uncommon to see people of rainbow hues walking around Huntsville. In addition to the discoloration nuisance, dust on the M16 line was always a health hazard, and the danger of fire and/or explosions was constantly present. Therefore, persons working in colored smoke were paid one grade higher than the corresponding job in other types of work. The extra pay helped to compensate for the danger, the dusty conditions, and the almost indelible dye. Fires were numerous, as many as 11 in two hours being recorded when yellow grenades were being made. The greatest contribution to colored smoke manufacture was obtained when oil was introduced into the dye before mixing the other components with it. This process of oiling the dye allowed the mix to be packed into the grenade without spurting and decreased the dust hazard to a very great extent. It also sped up production tremendously because of the ease of handling the mix. The first M23 rifle grenade (red) streamer was produced on 30 April 1944. The plant making it, capable of producing 6,000 grenades and packing 10,000 per 8-hour shift, shut down at the end of hostilities. Until September 1944, all M23’s were filled by hand, resulting in uneven fills. This, in turn, caused an erratic burning time. Satisfactory results were obtained when M18 mixing, filling, and pressing equipment was used to manufacture M23’s. Manufacture of M22 rifle grenades began on 14 March 1944. The plant used for this purpose was the same as that used for the M16 and M18 hand grenades. Production of this grenade continued until April 1945, when the yellow grenades posed some difficulties. The flaming was traced to the primer being used by Ordnance. A newly developed primer, called the M45, allowed production to resume on 9 July 1945. Canisters The M2 105-mm canisters for colored smokes were produced at Huntsville Arsenal for shipment to Redstone Arsenal, where they were assembled into base ejection shells, three canisters per shell. The final product was used by artillery for signal and identification purposes. The production of the M2 canisters began with the manufacture of red canisters on 4 May 1943. The violet followed on 6 May 1943, next came the green and orange on 9 May, and finally the yellow on 12 May 1943. Average production for an 8-hour day, based on 125 assigned to the entire operation yielded 4,000 each for orange and violet; 4,700 green; 5,200 red; and 3,200 yellow. The lower amount for yellow was caused by the fire hazard involved while running the yellow mix. As Ordnance requirements for colored shells decreased in 1945, the final M2 colored canister was produced at Huntsville Arsenal on 5 July 1945. |

|

Refuzing All hand grenades produced prior to July 1944 had been fused with M200 fuzes, which proved unsatisfactory in the field. As these fuzes were not waterproof, the percentage of duds in the field was excessive, particularly among grenades shipped to the Pacific Theater of Operation’. The munitions were returned to Huntsville Arsenal for installation of an improved fuze, the M201. The refuzing program began in June 1944 and continued sporadically until July 1945. The daily production varied greatly, depending on the type of grenade being run and the number of personnel available. A crew of 80 people (35 on the defuzing line and 45 on the refuzing line) could normally run 10,000-12,000 M14’s per 8-hour shift; 7,500-10,000 M8’s; or 7,500-10,000 M18’s.

Stenciling Each bomb, shell, or grenade filled had to be marked to indicate size, contents, lot, manufacture, and date. Original operating directives stipulated that this would be done by paint stenciling with spun copper or Monel stencils, but ordinary use by inexperienced operators proved hard on such stencils, which cost from $17 to $200 each. Engineering Service Division shops developed a galvanized sheet metal stencil costing about $15. Stencil paper masks, with figures and lettering cut on a machine for insertion in a pre-formed slot, allowed the stencil to be used continuously since only the paper inserts had to be changed for different marking.

FRED Project In January 1945, at the request of the Army Air Forces, the Chief of the Chemical Warfare Service directed Huntsville Arsenal to test liquid propellants and methods of using them in connection with the launching of JB-2 bombs. The JB-2 bomb was similar to the German V-1 bomb. The program, known as the "FRED Project," was to consider hydrogen peroxide nitromethane and associated catalysts, and fuming nitric acid and aniline. The Engineering Branch ended its investigations in September 1945.

|

|

IV. REVIEW OF WAR RECORD

Administrative Problems At the end of the war, Huntsville Arsenal listed its major problems. Those pertaining to personnel concerned the shortage of skills, the lack of trained managers, both military and civilian, the generally poor physical capabilities of the workers available, the converting of agricultural personnel into industrial operators and supervisors, frequent changes of personnel, and transportation difficulties that resulted in absenteeism. Administrative problems centered around inadequate local policies, over- and under-direction, coordination with higher authority, dual control by OC CWS and the Fourth Service Command, necessity of developing administrative procedures, lack of the best type of organization, and difficulties created by required reports. |

|

The organization of Huntsville Arsenal differed basically from that of the other three CWS arsenals (Edgewood, Pine Bluff, and Rocky Mountain), which were organized on the basis of separating operations according to mission, each mission being self-supporting, if possible, with service elements so located that they could support the most missions. Responsible officials at the Arsenal at the time believed that the ultimate in organization could not be accomplished at Huntsville Arsenal because qualified personnel capable of directing and assuming responsibility for the accomplishment of major objectives were not available. In view of the scarcity of managerial personnel, the Commanding Officer felt that a very close personal control by the commander was necessary for satisfactory administration. The policy was established to treat many situations individually, instead of formulating overall policies and requiring that these policies be administered at lower echelons. To the organization and methods specialist, it might seem that many of the principles of organization were violated for a specific or general reason. It is possible that the full importance of a good organization as a management tool was not recognized by management throughout the operation of Huntsville Arsenal as a manufacturing installation. Many unknown factors undoubtedly entered into decisions made concerning organization, but it is probably true that personalities involved frequently determined the organizational structures that were approved. This is contrary to the usual counsel of organizational experts who recommend that an organization be developed first and that key personnel be obtained to fit the organization. Considerable difficulty stemmed from the constant fluctuation in personnel, resulting from frequent transfers of officers, creation of new jobs, drafting of civilians, and high turnover rates occasioned by the expansion of numerous other facilities that also had production goals to meet. Even though care was exercised in the selection of key officer and civilian personnel, the fact that such personnel frequently departed and that the mission of the organization, particularly the procurement program, was subject to change without notice, created a condition which, in the opinion of the Arsenal commander, eliminated much of the possibility of delegating responsibility. However, the retention of decision-making at higher echelons, even on minor matters, prevented untrained personnel from getting the necessary experience that would eventually have enabled them to accept the responsibility that should have been delegated to them. An interesting sidelight concerning management bottlenecks pertained to the requirement that forms at Huntsville Arsenal had to be approved by the Control Division, Office of the Chief, CWS. Sometimes eight or ten endorsements were needed to secure approval of an operating form. This situation reportedly proved very disheartening to Huntsville Arsenal personnel who were aware that Redstone Arsenal had been delegated the authority to approve local forms. War Department and Army Service Forces policies on maintenance, repairs, and utilities caused considerable confusion at Huntsville Arsenal for these functions and affected the ability to make effective, timely decisions. Operations and available personnel at a post such as Huntsville Arsenal were radically different from those at a "normal" troop post, camp, or station. Policies, directives, and regulations prepared to apply to the latter type of installation were either not applicable to a manufacturing arsenal or had to be interpreted so broadly that their effectiveness was entirely lost. Having two "masters" was not an expediting factor. Considerable time and energy were spent in determining which had jurisdiction in certain matters—the service command or the. technical service. The Arsenal’s verdict on this matter: "Actual experience at this installation has demonstrated that dual operations, supervision, and administration are expensive, duplicating, and should be avoided if possible." The Arsenal also pointed to poor coordination between services, "particularly with respect to the Ordnance Department." In the majority of cases, orders received from Ordnance and OC CWS did not agree as to the quantity of production. This caused considerable administrative expense to correct and much waste in operating units due to administrative indecision. The Arsenal attributed the predicament to a lack of coordination between staff offices of the chiefs of the technical services.

Operational Problems The speed with which the Army built its war machine and attendant manufacturing facilities was a major factor in winning the war. However, construction forces, in their desire for speed, gave little consideration to the problems of operation and maintenance. This resulted in the replacement or revision of much of the original equipment and in the use of excessive operating personnel. Production difficulties arose from having to develop, from basic design or, in some cases, from "scratch," efficient production facilities; lack of adequate engineering in basic production equipment design; new production procedures; many types of end items to produce; the type of product, which presented many physical hazards; short-term operations (one and two months), including emergency requests; lack of a large program from which economies of mass production could be achieved; faulty components; and the dispersion of plants. Original design of the operating lines included practically no facilities for storage of components. (The mustard, white phosphorus, and M69-M74 filling plants were exceptions.) This condition made frequent deliveries on closely coordinated schedules necessary, to insure uninterrupted line production. One of the big problems was the disposal of obsolete and excess material. This occupied a considerable portion of storage space needed for current items. Igloo storage proved very unsatisfactory for current items because of the igloos’ geographical location, their size and shape, and the dampness in them that tended to deteriorate any stored material. The dispersal of warehouses, magazines, and igloos over many square miles tended to make supervision difficult. Also, most of the warehouses were ground level, and this necessitated much additional labor in loading and unloading materials. The lack of materials handling equipment such as lift trucks, conveyors, and carts seriously hindered proper handling. The Arsenal, like many another organization, was not free from packaging problems. The non-standard packaging of components received from district contractors caused many troubles. For example, parts for the E46 cluster, particularly the clamp, were usually thrown into an empty truck with no marking and no uniform stacking. The person who opened the doors of the trailer when it arrived at the Arsenal courted danger by running the risk of having the entire load shift upon him. In addition to this, three times as many people and many more hours were required to unload the truck. Many of the heavy parts were shipped in light wrapping paper and poorly constructed corrugated cartons, containing no marking and thus forestalling uniform storage in warehouses. Such shipments often resulted in "lost" parts simply through inability to identify them. Improper packaging also allowed metal components to rust and become absolutely unusable. In April 1942 when Huntsville Arsenal started to manufacture, production was dependent on the supply of components, available trained personnel, and the successful operation of the manufacturing plant or filling line. There were no schedules to meet or forecasts to make. The prevailing idea was to produce everything possible. This policy continued until May 1943. After that, definite schedules had to be established so that end items produced at the various arsenals would balance in a satisfactory manner. In forecasting production schedules, the usual procedure was to call a meeting of all interested division and department chiefs to discuss capabilities and requirements. A Redstone Arsenal representative always attended to assist in coordinating delivery of Ordnance components for filling with CWS material and to schedule Ordnance production consistent with line operations at both Arsenals. |

|

Summary During its lifetime, the Arsenal produced many new munitions and did some development work with good result. The Chief, CWS frequently requested Huntsville Arsenal to perform difficult production tasks to meet emergency conditions. While economy may have been sacrificed to expediency in some cases, the work was generally accomplished in sufficient time to meet the requirements of the situation. Taking into account the fact that very little experience was available upon which to base design, organization, or operation, the results achieved were remarkable. Although many things could have been done in a more unhurried atmosphere to improve administration and operation, wartime conditions did not permit a refined study of each situation before reaching a decision. But the fact remains that critical production dates were advanced and met. Production was doubled, tripled, or cut back as schedules changed rapidly to conform to changes in Army requirements. The large number and different types of items educed much emergency effort. It may be safely stated that Huntsville Arsenal was truly the industrial pioneer of the Chemical Warfare Service. The experience gained, both in the construction and operating phases, perhaps equaled its contribution in the production field in that it formed the basis for the success of later CWS arsenals.

|

|

V. DEMOBILIZATION, 1945

Impact on Mission and Manpower The major effect of V-E Day on Huntsville Arsenal was that production schedules for certain smoke munitions were altered to meet new requirements and increased emphasis was placed on the production of white phosphorus munitions, mustard bombs, and incendiary bombs. There were no personnel reductions. The impact of V-J Day was the immediate stoppage of all production activities except certain work in the Field Equipment Repair Shop and Chlorine Plant No. 1. On 20 August 1945, the Chief, Chemical Warfare Service issued instructions to put certain plants in ‘‘standby storage" and others in "standby under power." On 11 September this policy was changed to place all plants in standby storage, thereby reducing the Arsenal’s workload considerably. Lacking sufficient time to process reduction-in-force papers on personnel no longer needed, the Arsenal placed many on furlough pending the development of RIF procedures. A case in point was the Operations Division. On 9 August 1945, it had 2,197 per diem employees and 152 per annum employees. On 25 October, it had 59 and 36, respectively. How to effect an equitable reduction in force while some divisions were reducing rapidly, others maintaining their former strength, and some were increasing, posed a real problem. As already seen, the Operations Division cut back drastically, but Personnel, Transportation and Property proceeded more gradually. The Gulf Depot was acquiring additional activities, however, and a gas mask assembly plant was to be in operation by January 1946. Since the entire Arsenal, including the Depot, was one competitive area, the trick was to conduct a reduction in force without upsetting the functions of those organizations with work to be done. The demobilization picture was further confused by the return of a large number of veterans with re-employment rights. A number of voluntary resignations after 14 August offset this to some extent. Another complicating factor was that resignations and transfers of Civilian Personnel Division employees exceeded the need for reduction, leaving barely enough people to do the work and necessitating some overtime. The division’s 109 civilian employees on hand on 9 August had dwindled to 52 by 1 January 1946. The Fiscal Division suffered a hardship in demobilization because RIF quotas applied to this division took no consideration of the fact that fiscal matters—including records, accounts, and liquidations of obligations—would lag the rest of the demobilization program by about 120 days. In the procurement area, the main problem was the delay in getting decisions from using divisions as to whether or not material on order could be canceled. This in turn was a direct result of the indecision as to what the Arsenal’s status would be. If a clear-cut picture could have been furnished before V-J Day, contract terminations could have been made faster, with a saving to the Government. V-J Day and the period of demobilization brought a period of increased activity for the Property Division, as a double mission remained for completion. Early in l945, the division began an inventory of all maintenance and supply warehouses and the return of all stock cards to the stock records section as accountable records. The complete shutdown of manufacturing activities made hundreds of components surplus, and several thousands of maintenance items became surplus because of the curtailment of maintenance activities resulting from the shutdown of manufacturing plants. Declaration of surplus property of all kinds had begun with the institution of the Redistribution and Salvage Program in 1943. In order to expedite this two-fold mission, the Property Division requisitioned personnel from other divisions, particularly Operations. This influx of personnel lasted until early October, when a peak strength of 340 was reached. After that the division had to reduce to meet its December ceiling of 200 civilians. The Property Division had anticipated that, very soon after V-J Day, the shipment of component items, maintenance, and general operating supplies would cease as soon as shipments which were already en route had been received. It did not expect that termination inventories would be shipped to Huntsville Arsenal from CWS contractors and plants. However, it was soon learned that several million dollars’ worth of "goop" which remained from the M74 program would be shipped from a Chrysler Corporation plant at Evansville, Indiana, and it was necessary to lay out additional open storage areas for this material. Several new areas were selected, none of which was near the railroad tracks, so that considerable hauling was necessary. After the war, an additional duty given to the Safety Division was the investigation and compilation of claims submitted by Arsenal personnel against the Government for injuries sustained by them in the course of their employment. The Medical Department encountered extra work when it had to administer termination physical examinations to thousands of employees who were leaving the Arsenal. This assignment generated a greater workload for the Medical Department than it had had during full-scale production. Signal operations decreased significantly after V-J Day. The use of Government-owned teletypewriter equipment was discontinued in December 1945 because of reduced telegraphic traffic. Also, one shift was eliminated at the Gulf Depot, but this affected only one employee. A perplexing element impeding the demobilization of the Transportation Division was the lack of accurate information concerning the mission and extent of operations for the Arsenal as a whole after V-J Day. At first, the division made personnel reductions on the assumption that, should cut-backs be made too quickly, those that were left could work some overtime if necessary. Then an order practically eliminated overtime. In some cases, personnel had to be called back when others resigned. The greatest problem was trying to coordinate activities with other divisions, whose requirements were also indefinite. Apparently, from the beginning of the construction of Huntsville Arsenal, the function and place of the Arsenal in the postwar era was unknown. At least, the governing factors were not available prior to V-J Day. Therefore, local plans had to be developed rapidly after the policies of higher authority were clearly outlined. As these policies evolved gradually, attendant lost time and inefficiency resulted. However, in view of the sudden end of the war and the impact of the atomic bomb on political and military thinking, a certain amount of confusion concerning the future of an installation of this type was perhaps inevitable. Another demobilization problem that arose was the lack of understanding by employees and townspeople of RIF procedures followed in civil service. The use of efficiency ratings in determining retention points brought numerous complaints about the emphasis placed on these ratings as compared with seniority and about the accuracy and fairness of such ratings. Pressure from veterans’ organizations created numerous problems for the Commanding Officer in connection with discharging and employing veterans. As a result of uncertainty as to the duration of their jobs and a general letdown after the war, it became more difficult to obtain a good day’s work from some employees. This made demobilization costs higher than would have been the case if all employees performed according to their best ability. This situation was most apparent in the various maintenance and construction trades and labor groups. Demobilization of military personnel appeared to be too slow in that insufficient work was available to keep all officers busy enough to justify their presence. Some officers were extremely busy, especially those engaged in standby work, property disposal, and personnel work, while others, particularly those assigned to production activities, had little or nothing to do.