|

A comprehensive look into the vital role women have had in the history of Redstone Arsenal. Our premiere study on the women who worked the production lines during World War Two.

See Redstone Arsenal photos from the 1940's. Read Redstone Rocket article on "Teensie" Stroupe Read interview notes on Stacey Posey, sister of first women to be killed at Redstone Arsenal.

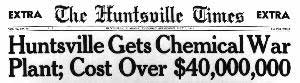

More than 50 years ago, fire trucks raced through Huntsville delivering an "Extra" edition of the local newspaper. The 3 July 1941 Huntsville Times' banner headline trumpeted the construction of a $40 million war plant on the southwestern edge of what was then a quiet town in northern Alabama. A month later, the Army's Chemical Warfare Service broke ground on a new chemical munitions manufacturing and storage facility named Huntsville Arsenal. Designed to supplement the production of the Army's only other chemical manufacturing plant at Edgewood Arsenal, Maryland, Huntsville Arsenal was the sole manufacturer of colored smoke munitions. The facility was also noted for its vast production of gel-type incendiaries. In addition, it manufactured toxic agents such as mustard gas, phosgene, lewisite, white phosphorous, and tear gas. During WWII more than 27 million items of chemical munitions having a total value of more than $134.5 million were produced at this war plant. |

The Ordnance Corps was attracted to the area by the presence of the Chemical Warfare Service installation. Recognizing the tremendous economy of locating a shell loading and assembly plant close to Huntsville Arsenal, on 8 July 1941 the War Department announced the establishment of a $6 million ordnance facility on a 4,000-acre tract east of and adjacent to the neighboring chemical munitions plant. It was hot and sultry in Huntsville on the morning of 25 October 1941, when MAJ Carroll D. Hudson walked to the center of a cotton field and turned over a shovelful of earth. This simple ceremony marked the beginning of construction of the Ordnance Corps' seventh manufacturing arsenal. Originally known as Redstone Ordnance Plant, the facility was redesignated Redstone Arsenal on 26 February 1943. During WWII Redstone Arsenal produced such items as burster charges, medium- and major-caliber chemical artillery ammunition, rifle grenades, demolition blocks, and bombs of varying weights and sizes. Between March 1942 and September 1945, over 45.2 million units of ammunition were loaded and assembled for shipment. The Army's impact on Huntsville was immediate and profound. But few, if any, of the town's citizens could have imagined what a change these installations and the war they were built to support would generate in the lives of the women living in Huntsville and the surrounding counties. |

World War II Workers, Redstone Arsenal |

|||

The Army's initial need for civilian employees was limited to engineers and skilled office personnel. The contractors selected to build the new plants also needed thousands of construction workers. Hundreds of men poured into Huntsville seeking employment. Within a week of the Army's selection of a site, almost 1,200 men had registered after "...the storming of the employment office...on Monday, [July 7th]." The local newspaper went on to report that, "Few women have registered, but approximately 200 of those placed on file...have been negroes." The labor market area on which the Army was dependent to recruit its work force was primarily agricultural. War Manpower Commission and U.S. Employment Office estimates showed that about 95 percent of the laboring class in Huntsville and the surrounding counties in 1940 were dependent directly or indirectly upon farming. Furthermore, the small percentage of industrial labor available locally was limited to textile manufacturing. In addition, of the more than 6,300 members of the total labor force in Huntsville still unemployed in 1940-1941, about 16 percent were women. These characteristics helped to impede the Army's recruitment of skilled labor, male or female, for its new production facilities.

World War II Workers, Redstone Arsenal

Several other factors also hampered the Army's efforts to hire needed personnel, including a lack of sufficient numbers of local secretarial and clerical personnel, and the migration of more qualified workers to defense plants on the coast. Another obstacle was the Army's inability to compete with the higher wages being paid by the contractors for certain types of jobs. Compounding these problems were such hindrances as the inadequacy of inexpensive local housing, poor transportation, poor secondary roads, and a large number of seasonal farm workers.

|

The emphasis in the first two years of production at Huntsville Arsenal was for male help of both races to do the heavy work, while white females were employed initially for production line work. Arsenal records noted that no demand was made for large numbers of black female employees until the local labor market was exhausted of white females. The lack of "...toilet facilities to take care of race distinctions peculiar to the South" was the reason given for this decision. By May 1944, Huntsville Arsenal's need for production, maintenance, and administrative personnel had accelerated greatly. That month civilian employment at the arsenal reached a WWII peak of 6,707 men and women. The ratio of male to female workers on 30 September 1944 was 63 percent male (52 percent white and 11 percent black) and 37 percent female (26 percent white and 11 percent black). The biggest recruitment problems in Huntsville faced by the Chemical Warfare Service prior to 1944 were the scarcity of qualified people with a background in chemistry and the unavailability of competent supervisory personnel. The latter situation was alleviated somewhat by the assignment of several newly commissioned Chemical Service officers. To obtain employees with the necessary chemical production background, arsenal authorities appealed first to technical schools and colleges throughout the southeast for applicants among recent graduates. Officials also selected several carefully chosen applicants and sent them to Edgewood Arsenal for training in methods of munitions and gas manufacture. This group became the nucleus for the training of other production personnel. |

World War II Workers, Redstone Arsenal |

|

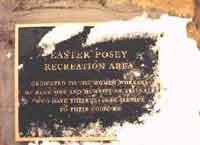

For quite some time, the basic training at Huntsville Arsenal was of the "on-the-job" variety. The urgent need to meet wartime production quotas left little time for operating officials to seriously consider any formal training program at the installation. To acquire additional locally trained skilled labor, the arsenal relied on technical courses offered by the University of Alabama and Auburn University. Conducted two nights a week for 12 weeks, these tuition-free "defense training courses" instructed men and women in such fields as basic accounting, structural design, mechanical and electrical maintenance, industrial management, chemistry, and engineering drawing. The first classes began in September 1941 and continued into the fall of 1943. In April 1942, the University of Alabama offered a course in chemical laboratory techniques "...for women only, who desire to qualify for jobs in defense laboratories..." By August 1942, local women were being urged to take advantage of the available technical training to prepare themselves to replace men in the work place who were needed for combat. Not only would women be helping themselves financially but they would be performing a patriotic service. Despite Huntsville Arsenal's efforts to ensure adequate pre-employment training, the installation continued to hire the majority of job seekers at the lowest possible grades, then promote them to higher paying positions as workers acquired more skills on the job. It was not unti l August 1944 that the arsenal established its own Civilian Training Department, which it patterned after the program instituted at neighboring Redstone Arsenal. The "supplementary training program" used by the Ordnance facility allowed employees to "...earn while they learned." A minimum of 10 hours of specialized training in their respective duties was provided to new employees before they actually began their assigned jobs. Special emphasis was placed on safety training. Also, applicants had to take a competitive exam prior to being hired to determine general intelligence and mechanical aptitude. While some leaders only urged women to continue such traditional roles as knitting, buying bonds, stretching rationed foodstuffs, and keeping up the nation's morale, others on the home front challenged women to join the ever-growing ranks of America's "production soldiers." In September 1942, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson made public his plan to double the number of women hired in war jobs. Newspaper accounts of that time reported that since 1 June 1942 the number of skilled women workers in the War Department had risen from 3 percent to 10 percent. Almost 35 percent of the department's unskilled workers were women. Uncertainty about the willingness and ability of American housewives to assume a larger defense role was expressed nationally as well as locally. One labor analyst warned that, "The employment of millions of untrained workers, including old men, youths, and housewives,...[would] inevitably result in a material and gradual dilution of labor skills, which...[meant] a decline in manpower output." The previously successful employment of women defense workers, according to this same analyst, was "...attributable to the fact that the more experienced and best adapted have naturally been the first employed. As...[the nation drew] more and more upon inexperienced and untrained homemakers, the average efficiency of women...[would] decline." The continual loss of male employees to the draft, accompanied as it was by the necessity of filling more jobs with women, impacted Huntsville Arsenal operations more than those of neighboring Redstone Arsenal. Many of the operating officials at the Chemical Warfare Service plant in 1942 opposed an increase in female hiring because the performance of women, especially black women, was an unknown quantity. The Redstone Arsenal commander, on the other hand, had publicized in February 1942 his intentions "...to use women employees wherever possible..." because men would be needed by the armed forces. The first two per diem female workers at Redstone were hired on 28 February 1942. By the close of December 1942, about 40 percent of the people working on the four Ordnance production lines were women. The percentage of female employees at Redstone Arsenal during 1944 averaged about 54 percent and jumped to a peak of 62 percent by September 1945. The women who sought employment at Huntsville and Redstone arsenals during WWII had economic, patriotic, and personal reasons for working. Although most of these women defense workers certainly appreciated the opportunity to bring in money to help support their families, it was the desire to contribute to the national war effort that gave these "soldiers of production" the incentive to work hard and long at their assigned tasks. Marie Owens, a 31-year- old employee of Huntsville Arsenal whose husband was in the Army, expressed to a local reporter in May 1943 that, "I am interested in carrying on here while the boys do the fighting over there. It is not a question with me as to what I do, nor how hard I work. The harder I work for them here, the sooner they will come home." This attitude of helping their husbands, sons, brothers, nephews, cousins, boyfriends, fiances, and neighbors to come out of the war unscathed as quickly as possible was commonplace among the women at both Army war plants. Eugenia Holman, a Redstone WOW (that is, Woman Ordnance Worker) explained her reasons for doing defense work in an open letter to a "friend" published in the Redstone Eagle post newspaper in May 1943, I remember when I came to work here last April. I wanted to win the war, naturally. Who didn't?...I thought of it in kind of an abstract way. Something that had to be done, but mostly by the boys at the front. You see, I hadn't learned then about the battles of production and assembly lines as I have now. I hadn't learned of the vital necessity of every able-bodied person doing their share no matter how small, and working! working! working!... The movement toward all-female work crews was a gradual one, particularly in those areas where women had never been assigned duty. Women-only crews, supervised by men, were not unusual at Redstone Arsenal even in 1942. By 1943, a woman supervisor and her "...all-girl crew of 15" at Huntsville Arsenal assembled smoke pots and acquired a reputation for being "...one of the most efficient crews at the arsenal. They...[were] usually ahead on production requirements and...[were] never known to fall behind." Although Huntsville's women defense workers were willing and able to do a "man's job," they still maintained their sense of femininity even under the most trying circumstances. For example, most of the women employed on the lines at both arsenals were provided nondescript coveralls and headgear to wear on the job. When the Redstone Arsenal burster line employees were issued new caps "...of a sheer material...in the shape of a Frenchman's beret," with matching face masks similar to surgical garb, the women were able to joke about their "new bonnet." A description of the new apparel concluded on the note that, "The caps are worn at the angle which is most becoming to the individual and some of the Bursterettes have really done well with this little problem." On the job at Huntsville and Redstone arsenals, women "...daily lived in this world of noise, heat [or cold], vibration, tension, and danger, where carelessness may cause an immediate accident or a disaster." During WWII, a total of five women were killed while on duty, three at Huntsville Arsenal and two at Redstone. Numerous others were hurt seriously, many of whom returned to work once their injuries had healed. Most of the women employed by the Army had to adjust not only to working outside the home but had to accustom themselves to working under conditions that would have tried the stamina and patience of experienced male industrial workers. In addition, many of the women workers at both arsenals contributed what little spare time they had to supporting a variety of home front activities such as Red Cross work, war bond drives, and packaging special seasonal boxes for distribution to soldiers overseas. With the successful conclusion of the war in Europe in May 1945 and the cessation of fighting in the Pacific in August, the need for munitions production abruptly ceased. Redstone Arsenal implemented its first reduction-in-force in June 1945, when about 200 employees were terminated as a "result of adjustments in production schedules..." The majority of those terminated were black women. By the end of October 1945, all of the Ordnance lines had been shut down and the number of female production employees was reduced to zero. Huntsville Arsenal placed about 500 operations employees, practically all of them women, on a 90-day furlough beginning 17 August 1945. This was followed by a massive layoff between 22 August and 1 September of more than 1,850 workers, again primarily women, who were furloughed so that the chemical service work force could be reduced by about one-third. The reason given for this decision was based on the belief that women were "...not suited for transfer to the heavy work in progress in Property and at the [Gulf Chemical Warfare ] depot," the installation's 7,700-acre storage facility.

The following article was written by

Dr. Kaylene Hughes in 1992.

One of the First Redstone Workers “Our first anniversary was on December 7, 1941. We had the whole day planned and then we got the news. Burton knew he was going to be drafted.” After World War II, production at both Redstone and Huntsville Arsenals ended. (Huntsville Arsenal was operated by the Army’s Chemical Corps and had a separate headquarters, commander, and staff). Stroupe’s husband Burton purchased excess lumber used to ship ordnance and built much of their present home with it. |