EXPLORER I

Table of Contents

The Army's Satellite Program

History of the Jupiter Rocket System

EXPLORER I photos

The story of Explorer I, the free world's first artificial satellite, goes beyond the traditional story of the Army team at Redstone Arsenal responding to the Soviet Union's launch of the Sputnik 1 on October 4, 1957. To truly understand the remarkable accomplishment made by the men and women of the greater Huntsville/Madison County community, we need to step back in time a bit further than 1957. On September 15, 1954, the Army Ordnance Missile Laboratories at Redstone Arsenal published the first true engineered thesis for a minimum satellite vehicle utilizing existing Army Ordnance Corps hardware. Written by Dr. Wernher von Braun, the thesis proposed using the REDSTONE missile as the main booster of a four-stage rocket for launching artificial satellites. The plan was later expanded into a joint Army-Navy proposal called Project Orbiter and submitted to the Assistant Secretary of Defense on January 20, 1955. However, 5 days later, President Dwight D. Eisenhower officially sanctioned another artificial earth satellite undertaking, the U.S. Navy's Project Vanguard, for the United States' contribution to the International Geophysical Year. As early as April 1956, the Army advised the Department of Defense that its JUPITER- C missile could orbit a satellite by the end of the calendar year as an alternate to Vanguard. In May 1956, however, the Defense Department informed the Army that it was not to initiate any plans or preparations for using any part of the JUPITER or REDSTONE programs as the basis for an orbital launch vehicle. As part of its reentry test vehicle program, the Army at Redstone flight tested a staged REDSTONE missile on September 20, 1956, that could have orbited the world's first satellite if permission had been granted to do so. Having proved that it had the necessary capability, the Army continued to offer its potential to launch a satellite as a backup to the Vanguard program, but again it was ordered to refrain from any efforts in this area. Dr. Ernst Stuhlinger, an original member of Von Braun's Team, revealed in a speech in July 1957 at the Army Science Symposium at the United States Military Academy, West Point, New York, that practically all components necessary for a successful satellite launch were available at Redstone Arsenal's Army Ballistic Missile Agency. These components, he said, were left from Project Orbiter. Instead, the Defense Department reaffirmed its close cooperation with Project Vanguard and denied that any of its research programs interfered with the intended tactical uses of the REDSTONE missile. As noted earlier, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik I, the world's first satellite, on October 4, 1957. A month later, they orbited a second, larger satellite, Sputnik II, on November 3, 1957. Five days later, on November 8, 1957, the Secretary of Defense, Neil McElory, directed the Department of the Army (and specifically the Army at Redstone Arsenal) to modify two JUPITER-C missiles and to attempt to place an artificial earth satellite in orbit by March 1958. The Navy made a last-ditch effort to launch their Vanguard. Project Vanguard faltered when it exploded on the launch pad on December 6, 1957. On January 31, 1958, just 84 days after receiving the mission, the Army Ballistic Missile Agency launched the first U.S. satellite-Explorer I-into orbit. With the successful launch of Explorer I, the Army embarked on an ambitious program which rapidly advanced U.S. interests and goals in the space arena. For example, the Army Ballistic Missile Agency placed additional Explorer satellites into orbit on 26 March 1958, 26 July 1958, and 13 October 1959. Also, on March 3,1959, Pioneer IV, a joint Army Ballistic Missile Agency/Jet Propulsion Laboratory project under the direction of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), achieved a velocity in excess of 24,560 miles per hour; passed within approximately 36,000 miles of the Moon; and traveled on to become the first U.S. satellite in permanent orbit around the Sun. And, the flight of monkeys Able and Baker on May 28, 1959, marked the first successful recovery of living beings after their return to earth from outer space. Their survival of speeds over 10,000 miles per hour was the first step toward putting a man into space. On July 1, 1960, the Army at Redstone formally lost all of its space-related missions, along with about 4,700 civilian employees (including the Von Braun team) and $100 million worth of buildings and equipment at Redstone Arsenal and Cape Canaveral to NASA's George C. Marshall Space Flight Center. At the activation ceremonies, Dr. von Braun, the new Director of the Center, remarked that "without the bountiful and courageous backing and support of the Army the free world would not jumped off into space nearly so soon." This article was taken from multiple sources contained in the Office of the Command Historian, US Army Aviation and Missile Command.

The Story of the Army's Satellite Program

As early as 1952, discussions were taking place on the possibilities of performing research by means of orbiting artificial earth satellites. These satellites would be instrumented with various types of measuring devices and radio equipment for transmitting the collected data to earth. It was obvious, however, that a powerful rocket engine, capable of producing enough thrust to accelerate the satellite to a speed of approximately 17,000 miles per hour, would be required. It was also apparent that it would be necessary to guide the satellite into a proper orbital plane. At that time, the state of the art was insufficient to the task. Then, on 25 June 1954, at the Office of Naval Research, Dr. Wernher von Braun proposed using the Redstone as the main booster of a 4-stage rocket for launching artificial satellites. He explained that this missile, using Loki II-A rockets in its three upper stages, would be capable of injecting a 5-pound object into an equatorial orbit at an altitude of 300 kilometers. Furthermore, since the launching vehicle would be assembled from existing and proven components within a relatively short time, the project would be an inexpensive undertaking. Further discussions and planning sessions culminated in the proposal's being adopted as a joint Army-Navy venture called Project Orbiter. The proposed project was submitted to the Assistant Secretary of Defense on 20 January 1955. However, 5 days later it became a dead issue after the President officially sanctioned another artificial earth satellite undertaking, Project Vanguard. Jupiter-C Because of the severe dynamic stresses and intense heat encountered by an object reentering the earth's atmosphere, the Army Ballistic Missile Agency early recognized the necessity of developing nose cone construction methods and materials to protect the payload during reentry. While extensive laboratory tests could prove the correctness of the approach taken in combating the reentry problem, scientists at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency still felt it necessary to conduct flight tests in order that the newly developed nose cone could be tested in an actual reentry environment. For these tests, the Agency used the composite rocket, first proposed for use in Project Orbiter. Despite the fact that the vehicle was a modified Redstone, the Agency designated it Jupiter-C because of its use in the Jupiter development program. The final stage, intended to orbit a satellite in its former configuration, was replaced by a scaled-down Jupiter nose cone. As a composite vehicle, it consisted of an elongated Redstone booster as the first stage and a cluster arrangement of scaled-down Sergeant rockets in the two solid stages. Several of these rockets were assembled, but only three were flown as Jupiter reentry test vehicles (RS-27 on 20 September 1956, RS-34 on 15 May 1957, and RS-40 on 8 August 1957). All three flights were considered to be successful, but only in the last firing was the nose cone recovered after it impacted at a point 1,161 nautical miles from the launch point. During its flight, the nose cone reached an altitude of 260 miles and survived temperatures, during reentry, of over 2000 Fahrenheit. As the first object to be retrieved from outer space, the nose cone was shown on national television by the President and then placed on permanent exhibition in the Smithsonian Institution. Explorer Satellites Dr. Ernst Stuhlinger of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency revealed in a speech at the Army Science Symposium at the United States Military Academy, West Point, New York, during July 1957 that practically all components necessary for a successful satellite launch were available at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency. These components, he said, were left from the earlier Project Orbiter and were also available from the Jupiter-C reentry test vehicle program. He also indicated that the Army Ballistic Missile Agency had an orbit evaluation program, first projected by the Guided Missile Development Division in 1954. It consisted of a computer program that would provide scientific data on the oblateness of the earth, on the density of the upper atmosphere, and on high altitude ionization. Among other things Dr. Stuhlinger noted in his speech was his observation that the 300-pound payload of the Jupiter-C reentry test vehicle missile could be converted to a fourth rocket stage plus an artificial earth satellite. In stating that the projected program had also included studies on high atmospheric conditions, on ionized layers of great altitudes, on the lifetime of satellites, on the earth's field of gravity, on mathematical studies of orbiting satellites, on recovery gear, on protective coverings for nose cones, and on radio-tracking and telemetering equipment (such as the highly sensitive micro-lock, a small continuous wave-radio transmitter developed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratories for Project Orbiter), Dr. Stuhlinger added strength to the rumors, rife at that time, that the Department of the Army was engaged in an unauthorized satellite project. Because of these rumors, the Secretary of Defense ordered the Department of the Army to refrain from any space activity. Following this, the Department reaffirmed its close cooperation with Project Vanguard and denied that any of its research programs interfered with the intended tactical uses of the Redstone. Then, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik I on 4 October 1957. A month later, the Soviet Union orbited a second, larger satellite. In this country, Project Vanguard faltered when it experienced repeated failures- The Secretary of the Army then submitted a proposal for a satellite program to the Secretary of Defense during October. He pointed out that eight Jupiter-C missiles were available and with slight modification would be capable of launching artificial satellites. He suggested that the Department of the Army be authorized to pursue a 3-phase satellite program using these Jupiter-C missiles. The first phase of the proposed program provided for launching two Jupiter-C missiles in which the nose cone would be replaced by a fourth stage containing instrumentation that would be packaged in a cylindrical container-he satellite. In the second phase of the proposed program, the Army would launch five of the Jupiter-C missiles that would orbit satellites equipped with television facilities. The third and last phase of the proposed program also involved the launching of a Jupiter-C. In it, the nose cone would be replaced by a 300-pound surveillance satellite. On 8 November 1957, the Secretary of Defense directed the Department of the Army to modify two Jupiter-C missiles and to attempt to place an artificial earth satellite in orbit by March 1958. Eighty-four days later, on 31 January 1958, the Army Ballistic Missile Agency launched the first U.S. satellite-Explorer I-into orbit. Following this successful launch, five more of these modified Jupiter-C missiles (subsequently redesignated Juno I) were launched in attempts to place additional Explorer satellites in orbit. Three of these attempts ended in failure. They were: Explorer II, RS-26, on 5 March 1958; Explorer V, RS-47, on 24 August 1958; and Explorer VI, RS-49, on 23 October 1958 The other two successful ones were Explorer III, RS~24, on 26 March 1958 and Explorer IV, RS-44, on 26 July 1958. During this satellite program, the Department of the Army gathered a great deal of knowledge about space. Explorer I gathered and transmitted data on atmospheric densities and the earth's oblateness. It is primarily remembered, though, as the discoverer of the Van Allen cosmic radiation belt. Explorer III also gathered data on atmospheric density while Explorer IV collected radiation and temperature measurements.

EXPLORER I Photos

Explorer I

Explorer I P. Van Allen and W. Von Braun

P. Van Allen and W. Von Braun Celebration in Huntsville

Celebration in Huntsville Explorer 1 Satellite

Explorer 1 Satellite Satellite Diagram

Satellite Diagram Jupiter C RS29

Jupiter C RS29 Loading satellite onto Jupiter C RS29

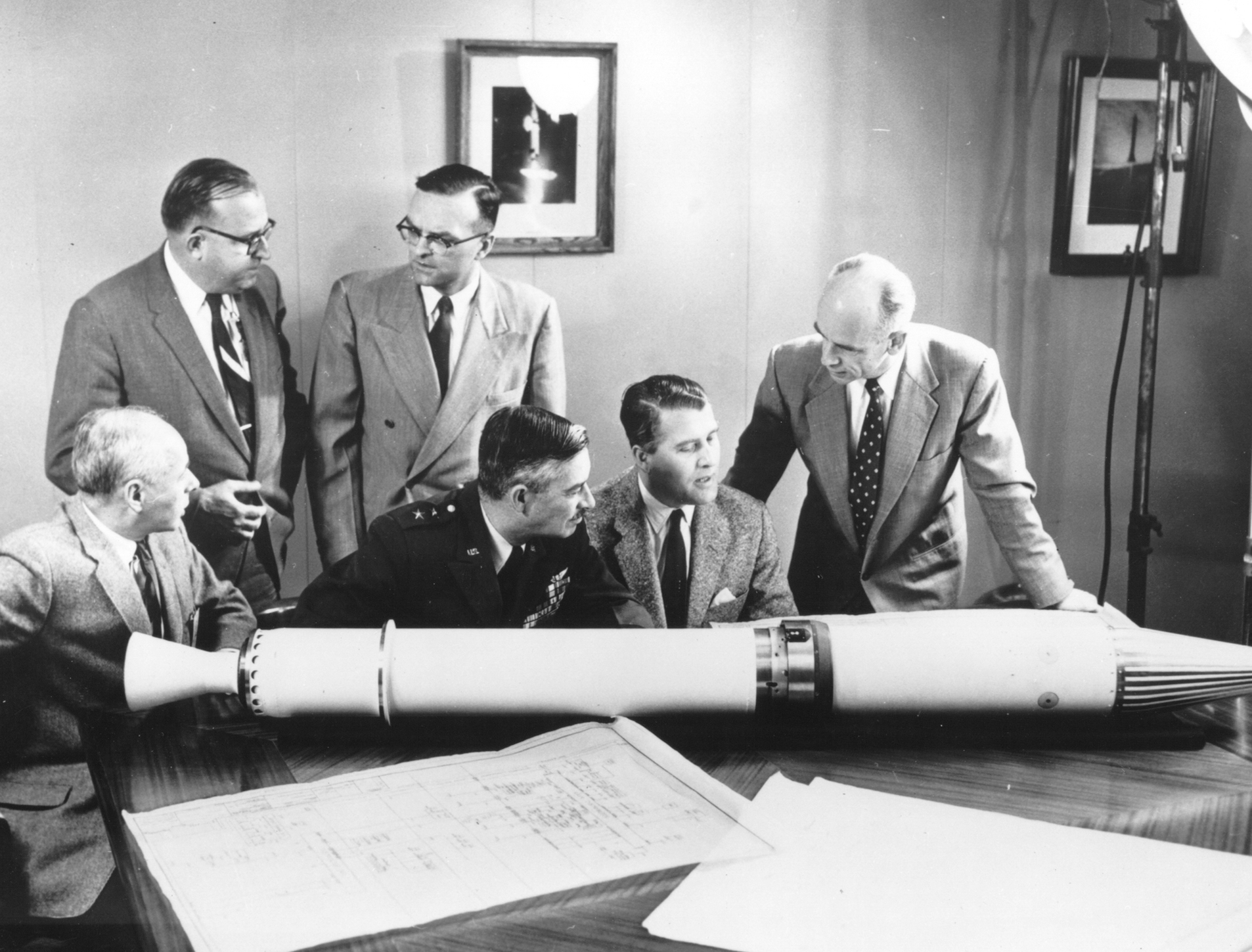

Loading satellite onto Jupiter C RS29 Von Braun Team with MG Medaris

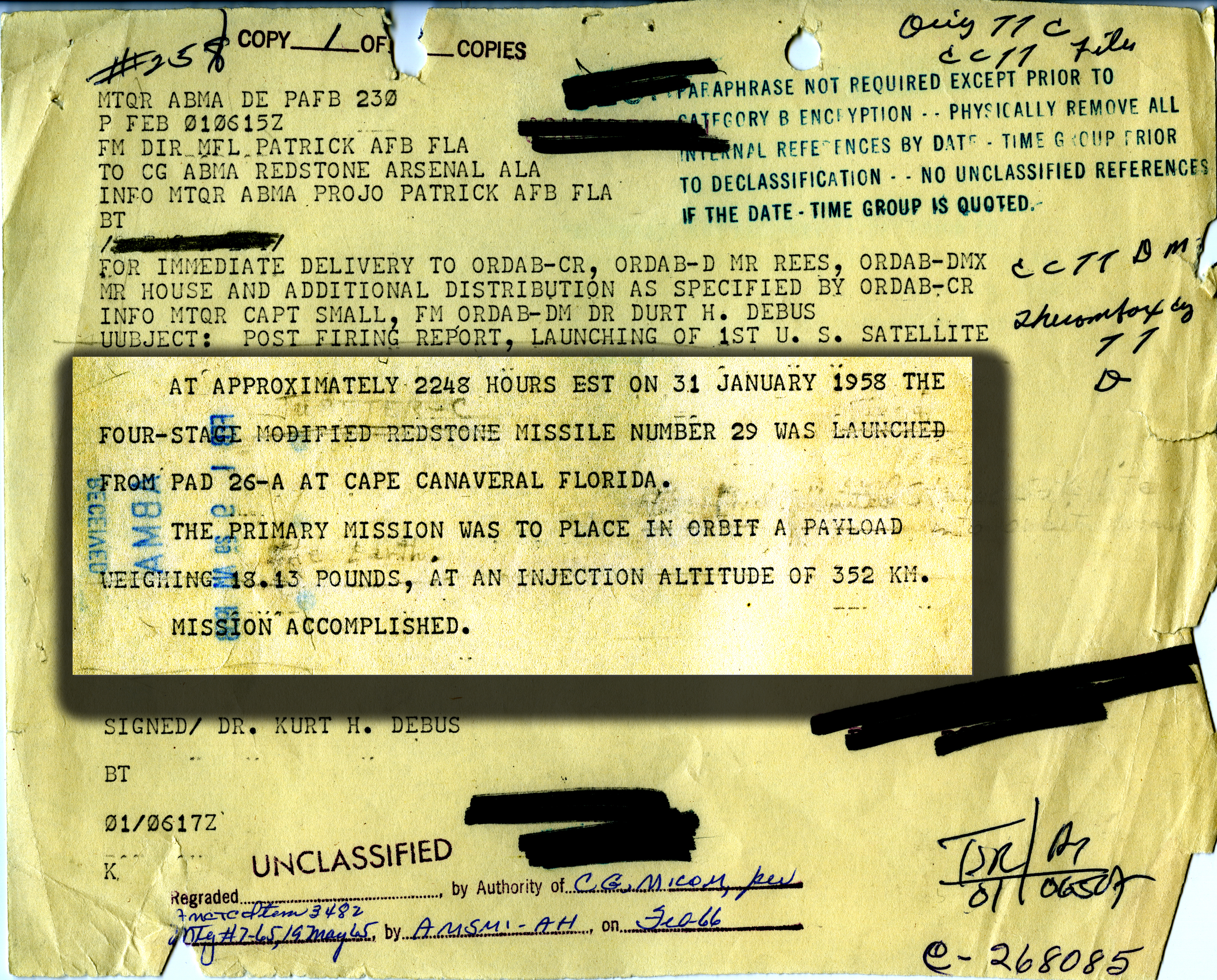

Von Braun Team with MG Medaris Message from Launch Facility

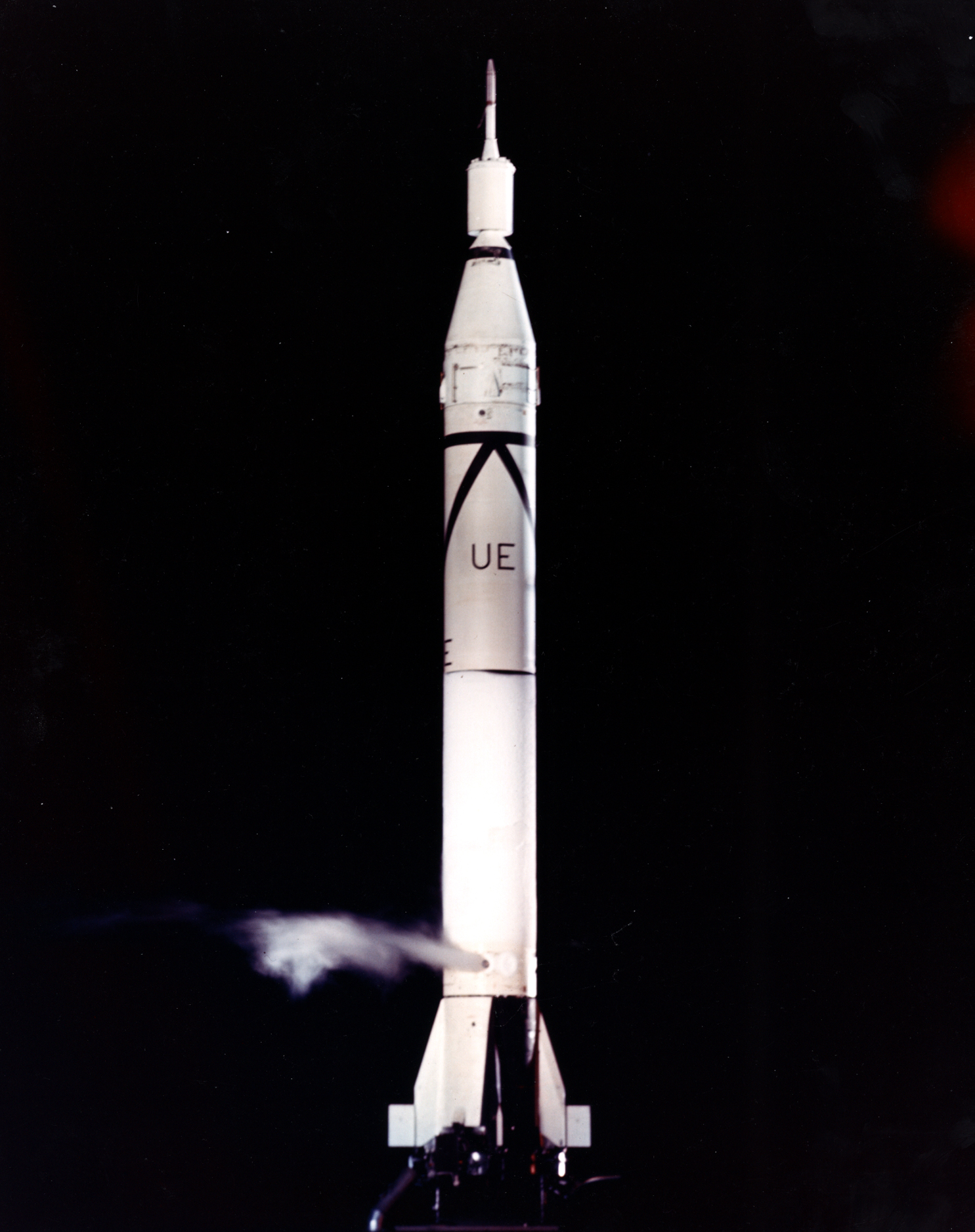

Message from Launch Facility Color photo of RS29

Color photo of RS29 P. Van Allen and W. Von Braun

P. Van Allen and W. Von Braun Pre launch activities for Explorer I satellite

Pre launch activities for Explorer I satellite SecDef McElroy touring Redstone Aresnal

SecDef McElroy touring Redstone Aresnal